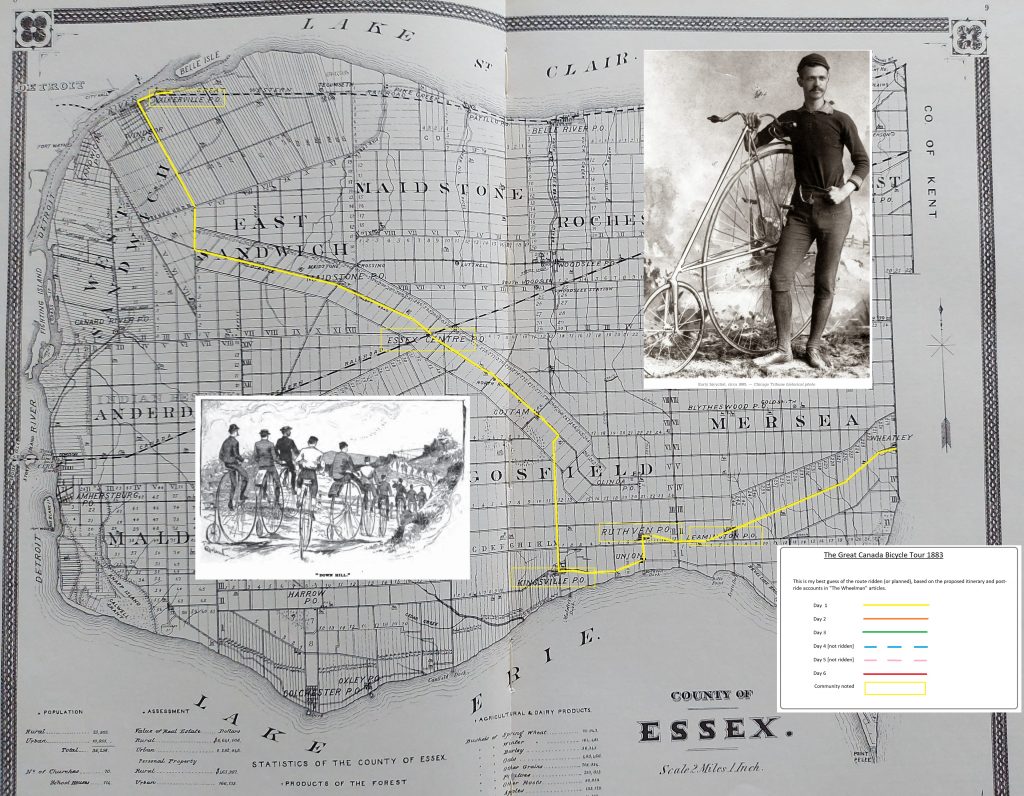

Next year will mark the 140th anniversary of an amazing group bicycle tour. Organized by the Chicago Bicycle Club, the Great Canada Bicycle Tour attracted 40 “practiced riders” who set out from Windsor on July 2nd, 1883 to bicycle a 640 km route across Southern Ontario.

Planning for the Great Canada Tour was announced in “The Wheelman” magazine in 1882, where the purpose was stated in most inspiring terms …

“For the promotion of bicycling in its most legitimate field, viz., its use as a practical vehicle of transportation through the country where the roads are good, its health-giving elements as an exercise, and ability of the wheel, where the rider is skilled in its economical management, to carry him over greater distances, and more enjoyably than can be done with the horse, thereby affording a most delightful and profitable means of spending a short vacation and interchange of views, practically demonstrated on the road, with fellow-wheelmen, the Chicago Bicycle Club inaugurates this tour, and cordially invites the wheelmen of the country to participate therein.”

The Great Canada Tour announcement reads very much like a modern Grand Randonnee “sign-up” website. Here are a few examples that Randonneurs will find amusing:

Ride Support:

“It is the intention to have a light covered wagon in attendance during the entire length of the tour, and therefore when starting out in the morning all baggage and other effects that the tourists desire to take with them will be promptly transferred from machines to the wagon.”

“In cases of break down to machines, repairs such as a blacksmith can accomplish can be readily made at frequent intervals en route, and delicate repairs can be accomplished at London, Hamilton, and Toronto… A set of tools for repairing machines will be included … and, so far as the standard machines are concerned, duplicate small parts liable to breakage, such as handle-bars, pedals, rear axles, spokes, springs, together with cement, will be carried, that no trifling break in a machine may mar the pleasure of the entire tour.”

Pre-ride:

“About sixty-five miles of roading in that vicinity [St Thomas and London] were wheeled over, and after a consultation with wheelmen who had been over every inch of the route, and knew every detail of the Canadian roads, a route was selected, daily mileage allotted and hotel accommodations agreed upon, that will take the tourists through all the principal places of interest in Ontario, over hard, smooth, and perfect roads, the daily allotments of mileage being those that have already been exceeded with comfort and ease by ordinary wheelmen, with fine hills easily climbed, except in a few instances, splendid coasting down the other side, a grand rolling country with varied scenery of hill, valley, woods, and streams, landing the tourists each evening at comfortable houses, with bills of fare equal to the emergency of the most voracious and particular appetite.”

…and of course, Expenses:

“Before the start is made … it will be expected every tourist will deposit with the treasurer… a sum at the rate of $1.25 per day while in Canada… The committee are assured by the Canada wheelmen, who have been over the same ground many times, that the expenses will not exceed $1.00 per day in Canada, in which case a refund will be made. This arrangement of appointing one man to settle the hotel bills on the tour will ensure the least inconvenience to the tourists, and favor the most liberal rates.”

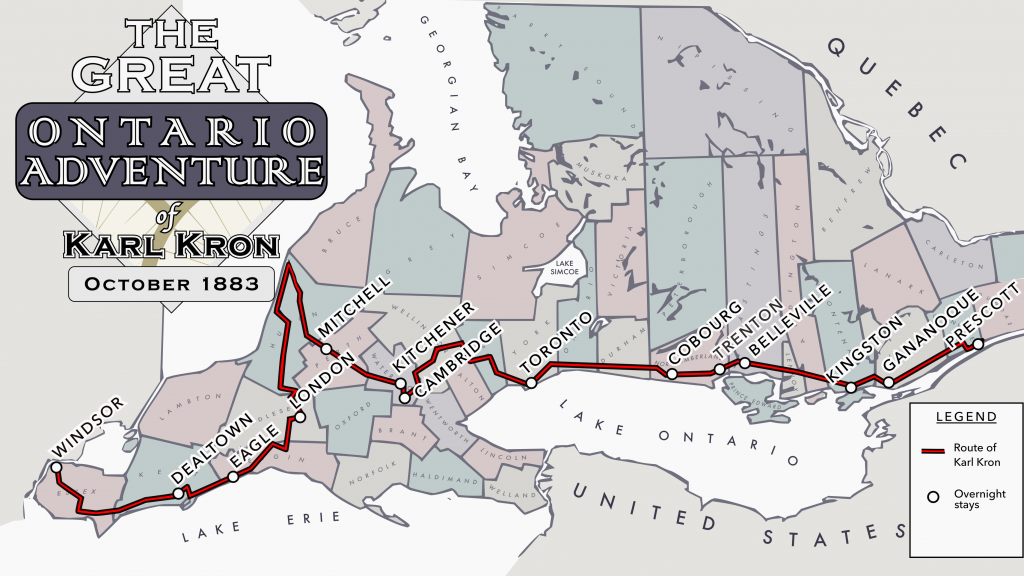

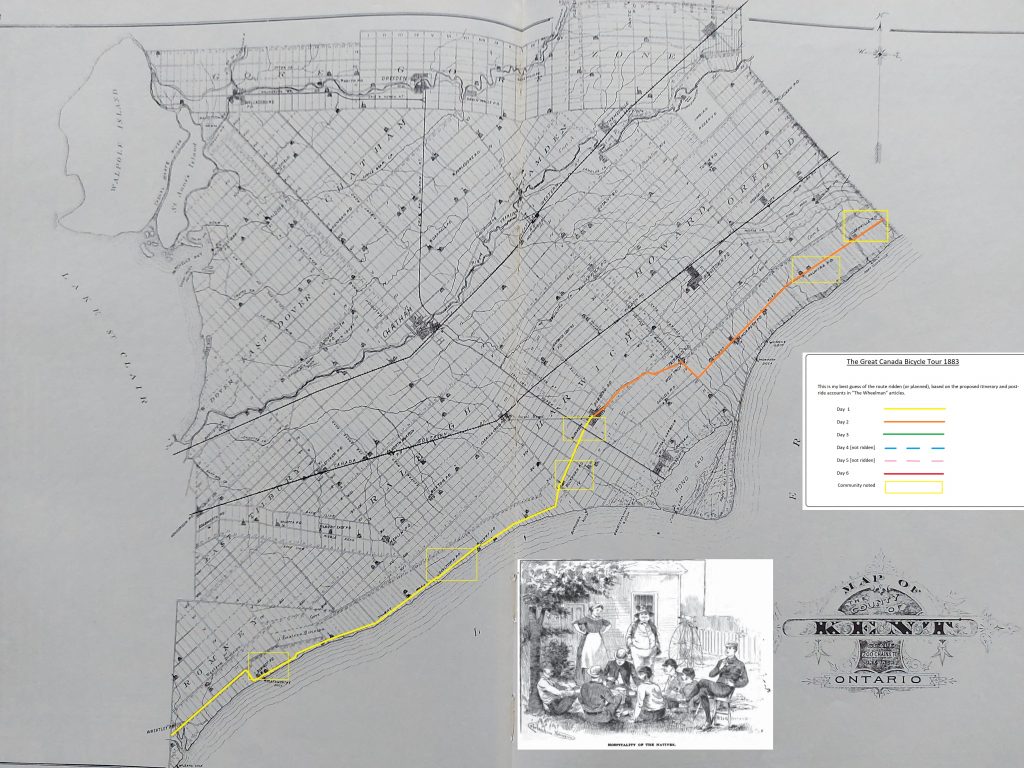

Here is a summary of the planned itinerary for the Great Canada Bicycle Tour:

“Monday, July 2d. … wheeling through [Detroit to] the upper ferry; thence across river to Walkerville and road to Essex Centre, nineteen miles; thence to Kingsville, and following the shore of Lake Erie, through Ruthven, Leamington, Mersea, Romney, Dealtown, Buckhorn to Blenheim, sixty-five miles from Detroit

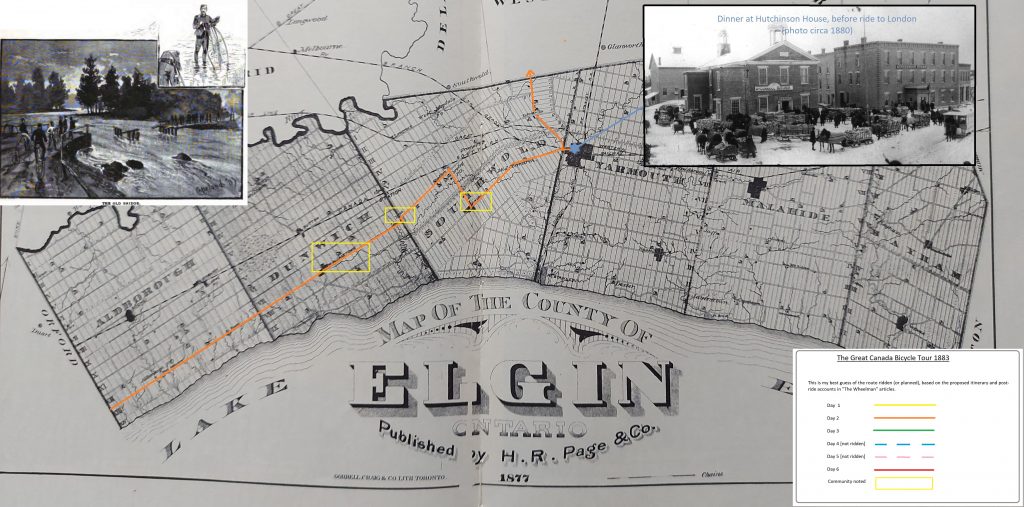

Tuesday, July 3d. From Blenheim to Wallacetown, forty miles.

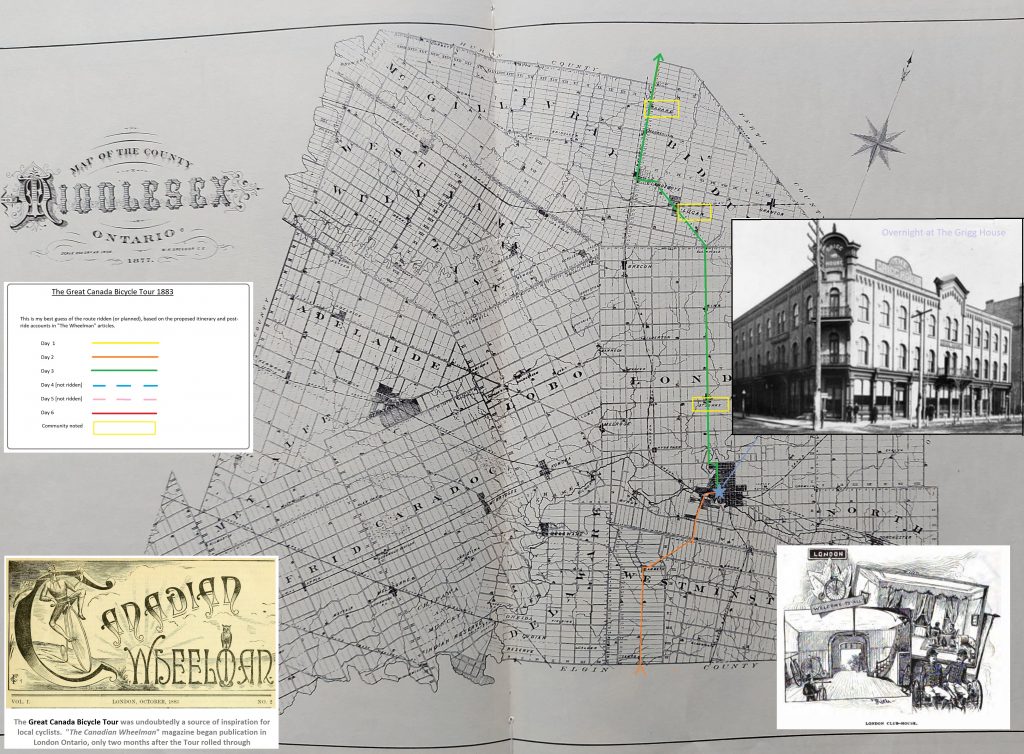

Wednesday July 4th. [to] St. Thomas, twenty-five miles. Trip is made over the Talbot road, the road from Kingsville to St. Thomas the oldest and finest track in Canada. Dinner will be taken in St. Thomas at the Hutchinson House, … From thence the route winds out of the magnificent St. Thomas valley over the gradually ascending high hills, … until abruptly reaching the summit of an easily climbed grade, London, with its towers, steeples, and elegant buildings, appears to view down in the valley below. Then follows a long coast and a couple of miles more travel to the Grigg House, which excellent hostelry will do the hospitable in the way of supper and lodging for the night.

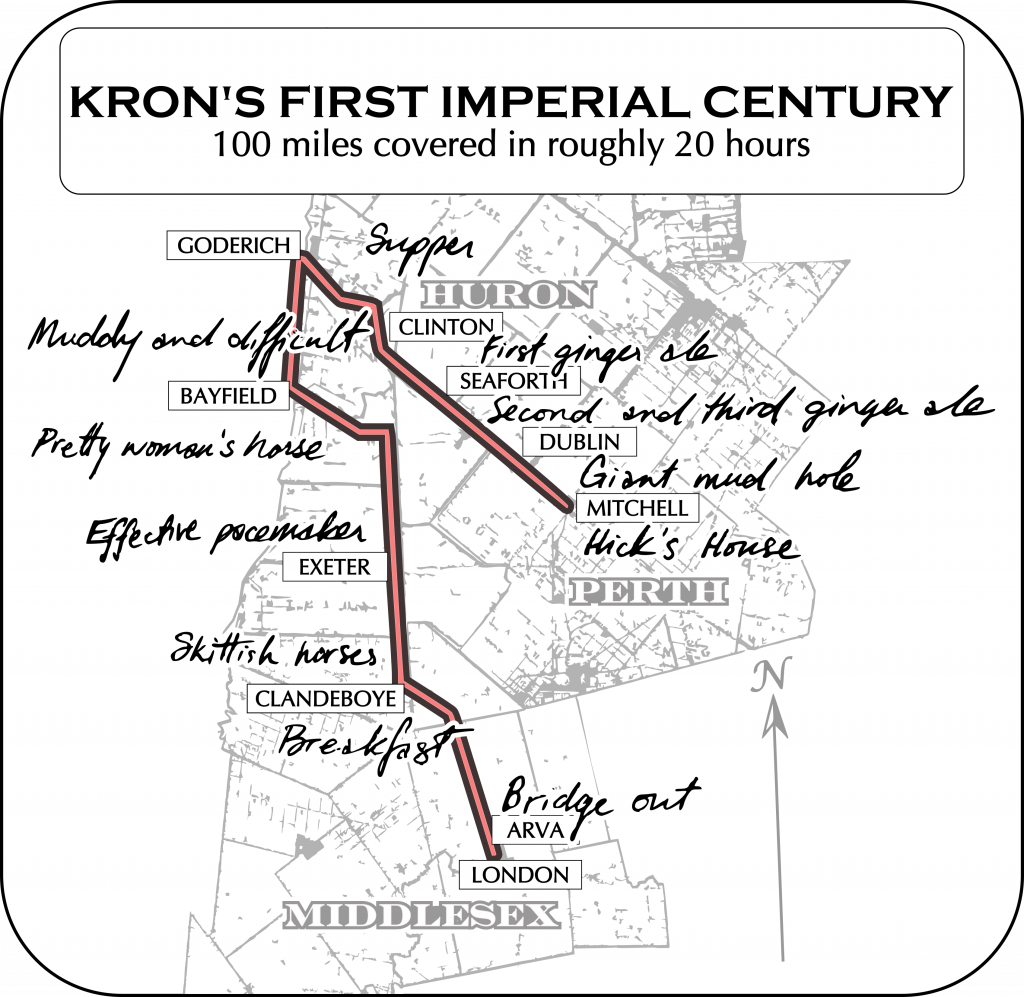

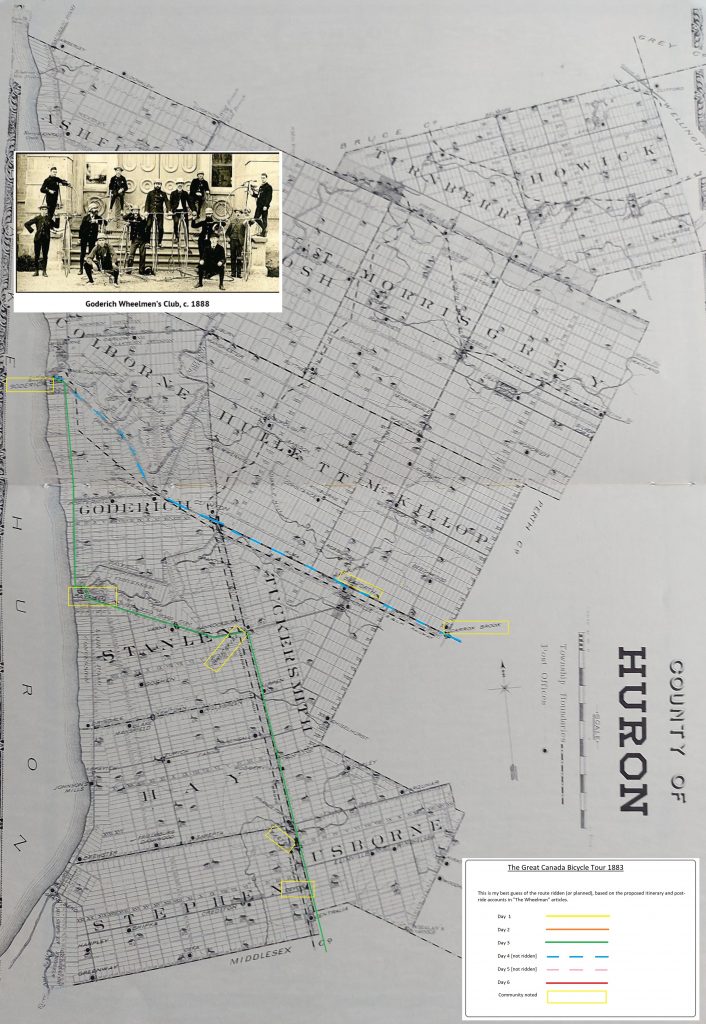

Thursday, July 5th. And now comes the event of the tour,—the wheel to Goderich, over the most famous road in America. This road can only be compared to asphalt, and many splendid runs have the Canadians made over it. The course laid out for the day is sixty-five miles, and passes through St. Johns [now Arva], Lucan, Ireland, Adare, and Devon to Exeter, thirty miles … mostly along the line of the Grand Trunk Railway. From Exeter the trip continues along the railway to Brucefield, when the road diverges to the shore of Lake Huron, which is followed to Goderich

Friday, July 6th. From Goderich the tour will continue in a straight line south-east … forty-four miles being the day’s allotment. The road follows closely along the line of the Grand Trunk Railway as far as Brantford. Dinner will be taken in Seaforth, A twenty-five mile spin in the afternoon through the picturesque villages of Carronbrooke and Mitchell brings the party to the commercial and railroad centre of the region, Stratford.

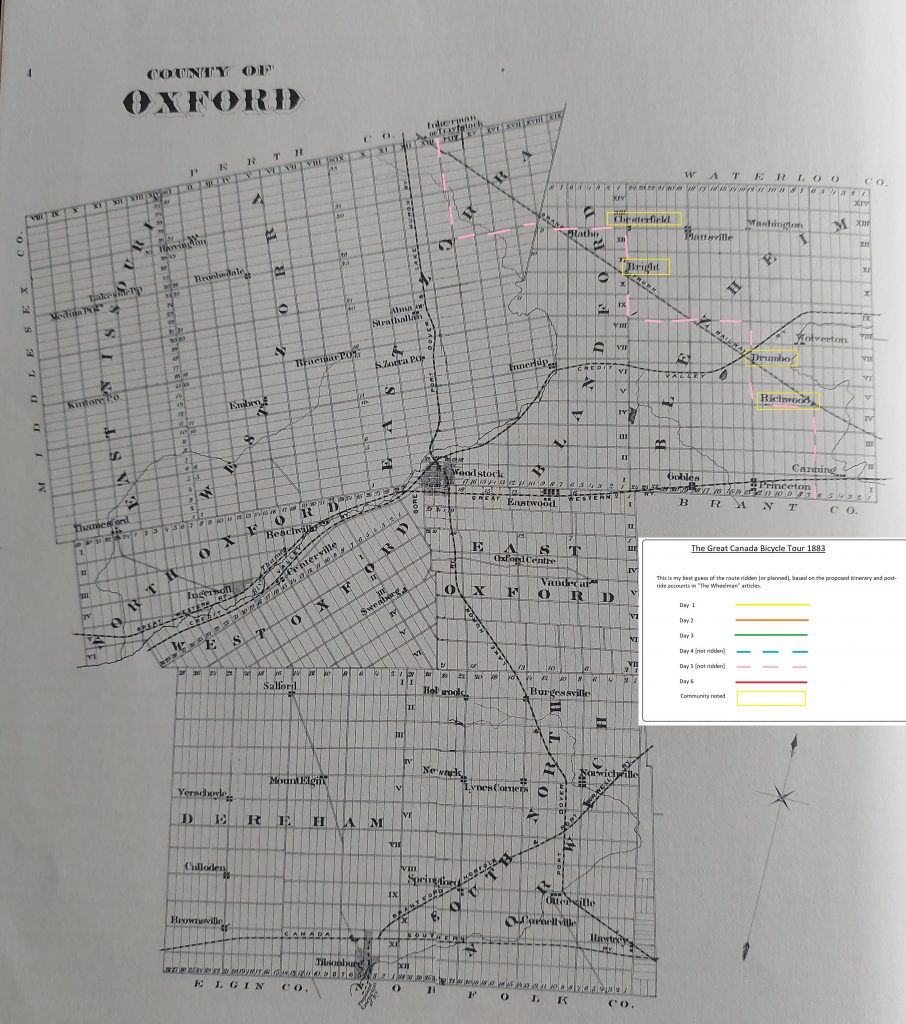

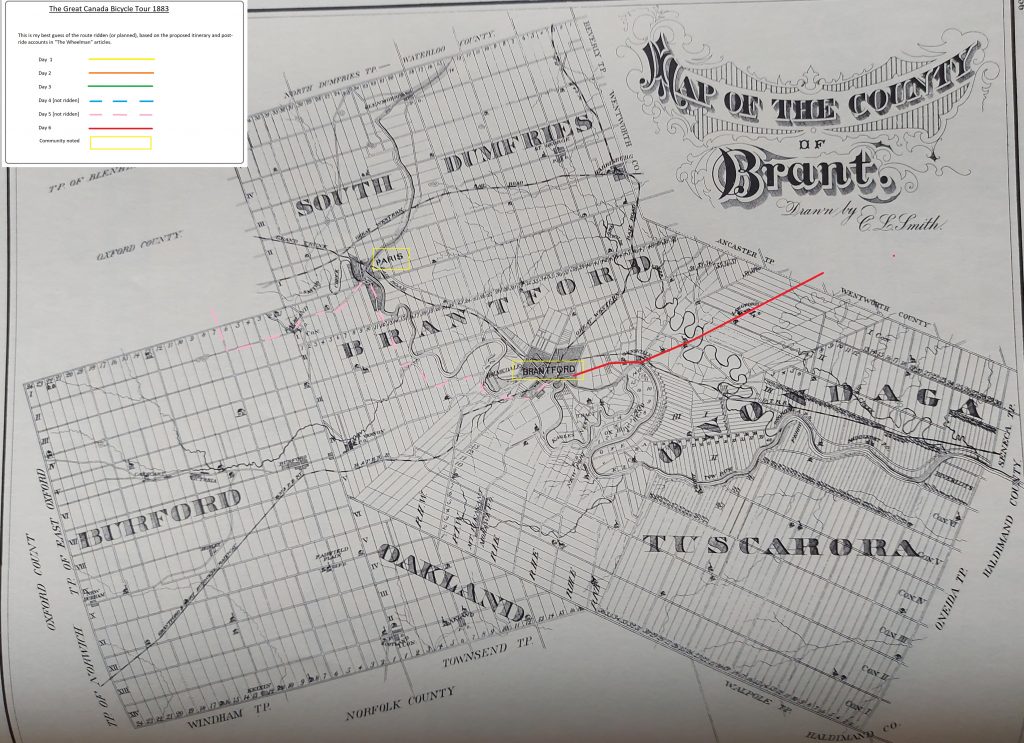

Saturday, July 7th. From Stratford down over the same road through Travistock (sic), Chesterfield, Bright, Drumbo, and Richwood to the large and thriving city of Paris, and from thence to Brantford, along the bank of the Speed river … The day’s journey … thirty-five miles.

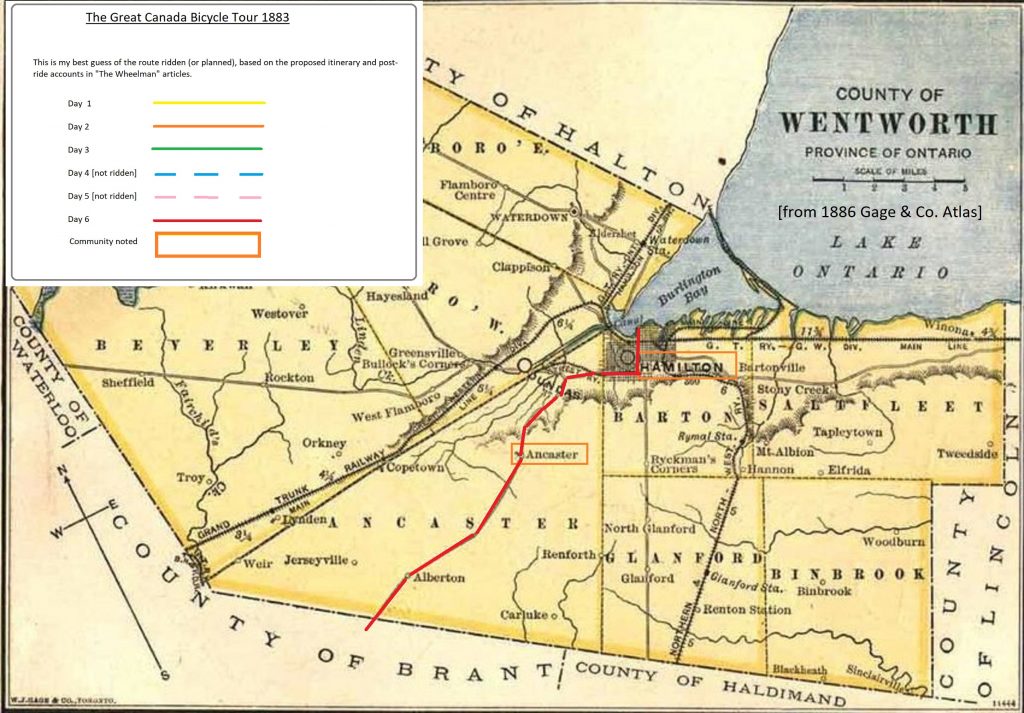

Sunday, July 8th. From Brantford, over a part plank and part gravel road, to Hamilton. This will be a short trip for the day, twenty-five miles, but may be considered by some as harder, on account of the nature of the road

Monday, July 9th. From Hamilton by boat to Toronto, arriving there in time for dinner, giving an entire afternoon at the metropolis before leaving on the evening steamer for Niagara.”

As with many modern long brevets, the best laid plans for the Great Canada Bicycling Tour were severely tested during the actual ride. Intense July storms, bridge wash-outs, and unanticipated bad roads resulted in schedule revisions, rider group separations, and extensive use of the sag wagon (“ambulance”). Already a day behind schedule in Goderich, a small group set out into rainstorms, hoping to cycle all the way to Brantford in one day. They were soon forced to turn back and, along with the other riders, ended up taking the train to Brantford. “We caught fleeting glimpses of the fine scenery at Paris and other points of interest, deepening our regret that we had missed riding through this romantic section of picturesque Canada”

A very detailed ride report of The Great Canada Bicycle Tour was presented in “Outing And The Wheelman” magazine of April-Sept. 1884. The entire two-part article is well worth reading. The author claims that “No intoxicating liquors of any sort were drunk, even at the banquets provided in the cities we visited”. With that one possible exception, the shenanigans and experiences described in the 1883 account bear remarkable similarities to present-day Ontario randonneuring! Here are some examples, with which I could particularly identify in my own randonneuring experience:

The thrill of cycling in a good tailwind:

“…this wind was so powerful that nearly the whole line rode with legs over handles, and with brakes down, a mile or two, at a racing speed, the utmost care being required to prevent collisions…”

Trying out new rain gear:

“…when it began to rain (he) put on his wheelman’s rubber suit…he was the envy of the whole line, till it was discovered that this suit possesses one fatal defect…There is no device…to let out the water which runs down the back of his neck, and fills all his pockets and swells out the legs”

Riding after a Fall:

“…Approaching Bayfield…one of the most expert riders of the party was run into by another wheelman…and hurled down an embankment five or six feet high. The pit of his stomach struck one of the handles, knocking the breath out of him, and his left shoulder was badly sprained… [We] procured him an ounce of Brandy at a wayside inn, after taking which he was able to mount unassisted, when he rode with one hand so rapidly [he caught up to the advance group]”

The Great Canada Tour was clearly important in fostering enthusiasm for bicycling, and the founding of many local wheelman clubs, throughout Southern Ontario. In each community, the arrival of the riders was greeted with large crowds, brass bands, and, at the overnight stops, civic receptions and banquets. This excellent 2016 article documents the impact of the Great Canada Tour’s arrival in Goderich.

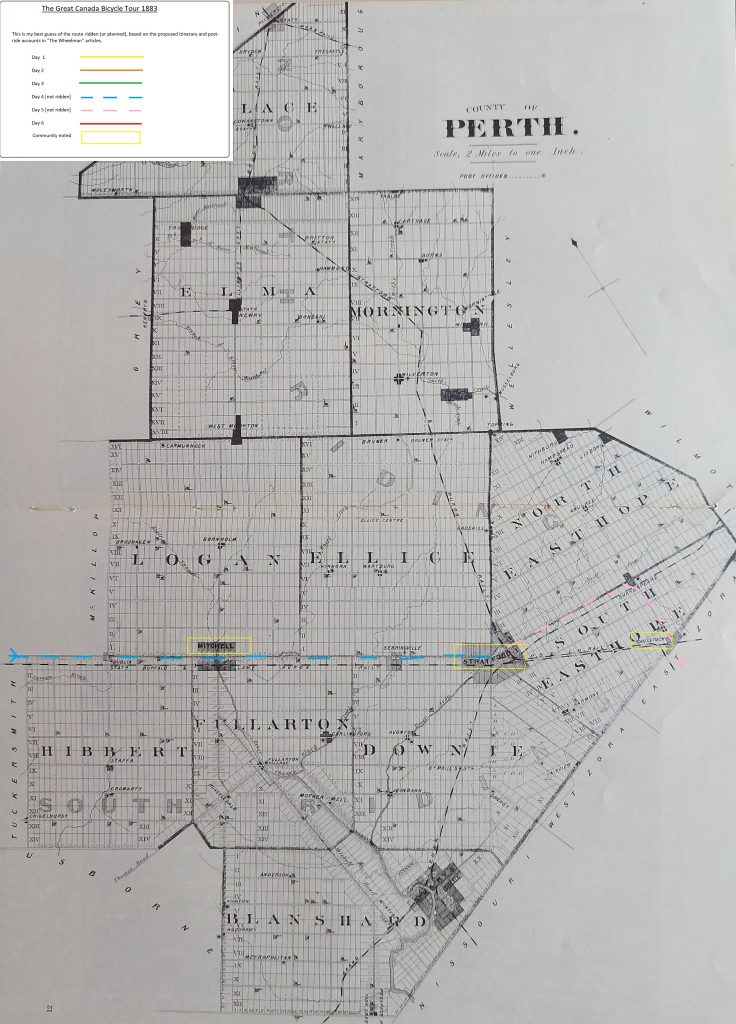

During the 1870s and ‘80s, illustrated “Historical Atlases,” with detailed county and township maps, were published for most Ontario counties. These County Atlases provide an excellent contemporary view into the routing and logistics issues faced by our Canada Tour bicyclists in the summer of 1883. (My father, Ross Cumming, republished many of these Historical County Atlases a century later, so I’m fortunate to have hard copies to pore over as I read the Great Canada Tour ride accounts). Based on the information in the “Wheelman” articles, I’ve charted my “best guess” of the route followed on the Great Canada Tour, in the maps below:

Clearly, the roads and municipalities of Ontario have changed drastically in 140 years! When our 1883 riders were cycling into St. Thomas or London, they were entering what we would now call the “city core” of those urban centres. At the other extreme, some villages with hotels, where the riders stopped for refreshment and accommodation, are now completely gone! Some roads ridden on the Canada Tour are now busy highways (Highway 3 “Talbot Trail” and Highway 4/Richmond Street) and others have long ago disappeared.

If we wanted to retrace the Great Canada Bicycle Tour, and rediscover the challenges and experiences of those hardy cyclists, what route would we take today? I have drafted a route which follows the (assumed) original route as closely as possible, and visits the significant landmarks and buildings identified in the original Canada Tour accounts:

Re-riding the 1883 Great Canada Bicycle Tour (rwgps)

As Randonneurs will suspect, it is no coincidence that this draft route is just north of 600 km in length! If there is interest among Ontario Randonneurs, a 2023 600 km Brevet or Permanent commemorating the 140th anniversary of the Great Canada Bicycle Tour could be as much fun as the 1883 original:

“The entire tour was ONE CONTINUOUS FROLIC OF FOUR HUNDRED MILES, through a strange and lovely country; and over each day’s run the imps of innocent fun and enjoyment presided…

…upon the termination of the tour…it was found that all [riders], except two, had gained weight during the trip; while all, without exception, had gained in health, elasticity of body and spirits, strength, activity, and vigor”

Of course, I make no promises that “no intoxicating liquors of any sort” will be consumed at the end of the ride.